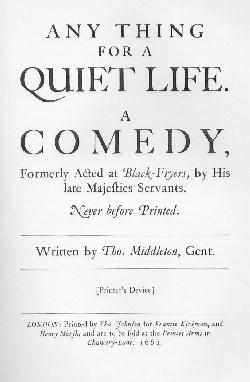

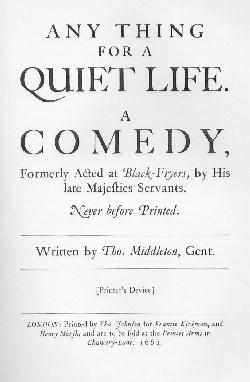

Anything

for

a

Quiet

Life

* * *

Dramatis Personae

Lord BEAUFORT

SIR FRANCIS Cressingham, an alchemist

OLD FRANKLIN, a country gentleman

George CRESSINGHAM, son to Sir Francis

FRANKLIN, a sea captain, son to Old Franklin, and companion to

George Cressingham

Master Water CHAMLET, a citizen

KNAVESBEE, a lawyer, and pander to his wife

SAUNDER, steward to Sir Francis

GEORGE and RALPH, two prentices to Water Chamlet

A SURVEYOR

Sweetball, a BARBER

[Toby, the] Barber's BOY

FLESHHOOK and COUNTERBUFF, a sergeant and a yeoman

[MARIA and EDWARD,] two children of Sir Francis Cressingham, nurs'd

by Water Chamlet

[Three CREDITORS named Pennystone, Phillip, and Cheyney]

LADY CRESSINGHAM, wife to Sir Francis

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM, wife to George Cressingham, disguised as]

Selenger, page to the Lord Beaufort

RACHEL, wife to Water Chamlet

SIB, Knavesbee's wife

MARGARITA, a French bawd

Acts and Scenes

I.i. Sir Francis Cressingham's house

II.i. Knavesbee's house

II.ii. Chamlet's shop

II.iii. Outside Sweetball's house

II.iv. A chamber in Sweetball's house

III.i. Lord Beaufort's house

III.ii. A street outside a tavern

IV.i. Sir Francis's house

IV.ii. Before Knavesbee's house

IV.iii. Chamlet's shop

V.i. Before Sir Francis's house

V.ii. A street outside Lord Beaufort’s house

PROLOGUE

Howe'er th' intents and appetites of men

Are different as their faces, how and when

T' employ their actions, yet all without strife

Meet in this point: Anything for a Quiet Life.

Nor is there one, I think, that's hither come

For his delight, but would find peace at home

On any terms. The lawyer does not cease

To talk himself into a sweat without pain,

And so his fees buy quiet, 'tis his gain:

The poor man does endure the scorching sun,

And feels no weariness, his day-labour done,

So his wife entertain him with a smile,

And thank his travail, though she slept the while.

This being in men of all conditions true,

Does give our play a name; and if to you

It yield content, and usual delight,

For our parts we shall sleep secure tonight.

I.[i. Sir Francis Cressingham's house]

Enter the Lord Beaufort and Sir Francis Cressingham.

BEAUFORT

Away, I am asham'd of your proceedings,

And, seriously, you have in this one act

Overthrown the reputation the world

Held of your wisdom.

SIR FRANCIS

Why, sir?

BEAUFORT

Can you not see

Your error? That having buried so good a wife

Not a month since, one that--to speak the truth,

Had all those excellencies which our books

Have only feign'd to make a complete wife,

Most exactly in her in practice--and to marry

A girl of fifteen, one bred up i' th' court,

That by all consonancy of reason, is like

To cross your estate. Why, one new gown of hers,

When 'tis paid for, will eat you out of the keeping

Of a bountiful Christmas. I am asham'd of you,

For you shall make too dear a proof of it,

I fear, that in the election of a wife,

As in a project of war, to err but once

Is to be undone forever.

SIR FRANCIS

Good my lord,

I do beseech you let your better judgment

Go along with your reprehension.

BEAUFORT

So it does,

And can find nought to extenuate your fault,

But your dotage: you are a man well sunk in years,

And to graft such a young blossom into your stock,

Is the next way to make every carnal eye

Bespeak your injury. Troth, I pity her too;

She was not made to wither and go out

By painted fires, that yields her no more heat

Than to be lodg'd in some bleak banqueting house

I' th' dead of winter. And what follows then?

Your shame, and the ruin of your children, and there's

The end of a rash bargain.

SIR FRANCIS

With your pardon,

That she is young is true; but that discretion

Has gone beyond her years, and overta'en

Those of maturer age, does more improve

Her goodness. I confess she was bred at court,

But so retiredly, that as still the best

In some place is to be learnt there, so her life

Did rectify itself more by the court chapel

Than by the office of the revels; best of all virtues

Are to be found at court, and where you meet

With writings contrary to this known truth,

They are framed by men that never were so happy

To be planted there to know it: for the difference

Between her youth and mine, if you will read

A matron's sober staidness in her eye,

And all the other grave demeanour fitting

The governess of a house, you'll then confess

There's no disparity between us.

Enter Master Water Chamlet.

BEAUFORT

Come, come, you read

What you would her to be, not what she is.

Oh, Master Water Chamlet, you are welcome.

CHAMLET

I thank your lordship.

BEAUFORT

And what news stirring in Cheapside?

CHAMLET

Nothing new there, my lord, but the Standard.

BEAUFORT

Oh, that's a monument your wives take great delight in; I do hear

you are grown a mighty purchaser. I hope shortly to find you

a continual resident upon the north aisle of the Exchange.

CHAMLET

Where? With the Scotchmen?

BEAUFORT

No, sir, with the aldermen.

CHAMLET

Believe it, I am a poor commoner.

SIR FRANCIS

Come, you are warm, and blest with a fair wife.

CHAMLET

There's it: her going brave has the only virtue to improve my

credit in the subsidy book.

BEAUFORT

But I pray, how thrives your new plantation of silkworms, those

I saw last summer at your garden?

CHAMLET

They are remov'd, sir.

BEAUFORT

Whither?

CHAMLET

This winter my wife has remov'd them home to a fair chamber, where

diverse courtiers use to come and see them, and my wife carries

them up; I think shortly, what with the store of visitants, they'll

prove as chargeable to me as the morrow after Simon and Jude,

only excepting the taking down and setting up again of my glass

windows.

BEAUFORT

That a man of your estate should be so gripple-minded, and repining

at his wife's bounty!

SIR FRANCIS

There are no such ridiculous things i' th' world as those love

money better than themselves; for though they have understanding

to know riches, a mind to seek them, and a wit to find them, and

policy to keep them, and long life to possess them, yet commonly

they have withal such a false sight, such blear'd eyes, all their

wealth when it lies before them does seem poverty, and such a

one are you.

CHAMLET

Good Sir Francis, you have had sore eyes too: you have been a

gamester, but you have given it o'er, and to redeem the vice belong'd

to't, now you entertain certain [parcels] of silenc'd ministers,

which I think will equally undo you. Yet should these waste you

but lenitively, your devising new watermill[s] for recovery of

drown'd land, and certain dreams you have in alchemy to find the

philosopher's stone, will certainly draw you to th' bottom. I

speak freely, sir, and would not have you angry, for I love you.

SIR FRANCIS

I am deeply in your books for furnishing my late wedding. Have

you brought a note of the particulars?

CHAMLET

No, sir; at more leisure.

SIR FRANCIS

What comes the sum to?

CHAMLET

For tissue, cloth of gold, velvets and silks, about fifteen hundred

pounds.

SIR FRANCIS

Your money is ready.

CHAMLET

Sir, I thank you.

SIR FRANCIS

And how does my two young children, whom I have put to board with

you?

BEAUFORT

Have you put forth two of your children already?

SIR FRANCIS

'Twas my wife's discretion to have it so.

BEAUFORT

Come, 'tis the first principle in a mother-in-law's chop-logic

to divide the family, to remove from forth your sight the object[s]

that her cunning knows would dull her insinuation. Had you been

a kind father, it would have been your practice every day to have

preach'd to these two young ones carefully your late wife's funeral

sermon. 'Las, poor souls, are they turn'd so soon a-grazing?

Enter George Cressingham and Franklin.

CHAMLET

My lord, they are plac'd where they shall be respected as mine

own.

BEAUFORT

I make no question of it, good Master Chamlet.

[To Sir Francis] See here your eldest son, [George] Cressingham.

SIR FRANCIS

You have displeas'd and griev'd your mother-in-law,

And till you have made submission and procur'd

Her pardon, I'll not know you for my son.

CRESSINGHAM

I have wrought her no offense, sir. The difference

Grew about certain jewels which my mother,

By your consent, lying upon her deathbed,

Bequeath'd to her three children; these I demanded,

And being denied these, thought this sin of hers,

To violate so gentle a request

Of her predecessor, was an ill foregoing

Of a mother-in-law's harsh nature.

SIR FRANCIS

Sir, understand

My will mov'd in her denial: you have jewels,

To pawn or sell them. Sirrah, I will have you

As obedient to this woman as to myself;

Till then, you are none of mine.

CHAMLET

Oh, Master George,

Be rul'd, do anything for a quiet life!

Your father's peace of life moves in it too.

I have a wife: when she is in the sullens,

Like a cook's dog that you see turn a wheel,

She will be sure to go and hide herself

Out of the way dinner and supper, and in

These fits Bow Bell is a still organ to her.

When we were married first, I well remember,

Her railing did appear but a vision,

Till certain scratches on my hand and face

Assur'd me it was substantial. She's a creature

Uses to waylay my faults, and more desires

To find them out than to have them amended.

She has a book, which I may truly nominate

Her Black Book, for she remembers in it

In short items all my misdemeanours,

As: Item, such a day I was got fox'd with foolish metheglin in

the company of certain Welsh chapmen; item, such a day being at

the Artillery Garden, one of my neighbours in courtesy to salute

me with his musket, set afire my fustian-and-apes breeches; such

a day I lost fifty pound in hugger-mugger at dice in the quest-house;

item, I lent money to a sea captain on his bare "Confound

him, he would pay me again the next morning," and such like,

For which she rail'd upon me when I should sleep,

And that's, you know, intolerable, for indeed

'Twill tame an elephant.

CRESSINGHAM

'Tis a shrewd vexation,

But your discretion, sir, does bear it out

With a month's sufferance.

CHAMLET

Yes, and I would wish you

To follow mine example.

FRANKLIN

Here's small comfort,

George, from your father: here's a lord whom I

Have long depended upon for employment; I will see

If my suit will thrive better. [To Beaufort] Please your

lordship,

You know I am a younger brother, and my fate,

Throwing me upon the late ill-starr'd voyage

To Guiana, failing of our golden hopes,

I and my ship address'd ourselves to serve

The duke of Florence.

BEAUFORT

Yes, I understood it so.

FRANKLIN

Who gave me both encouragement and means

To do him some small service 'gainst the Turk;

Being settled there, both in his pay and trust,

Your lordship, minding to rig forth a ship

To trade for the East Indies, sent for me,

And what your promise was, if I would leave

So great a fortune to become your servant,

Your letters yet can witness.

BEAUFORT

Yes, what follows?

FRANKLIN

That for aught I perceive, your former purpose

Is quite forgotten: I have stayed here two months

And find your intended voyage but a dream,

And the ship you talk of as imaginary,

As that the astronomers point at in the clouds.

I have spent two thousand ducats since my arrival;

Men that have command, my lord, at sea cannot live

Ashore without money.

BEAUFORT

Know, sir, a late purchase

Which cost me a great sum has diverted me

From my former purpose; besides, suits in law

Do every term so trouble me by land,

I have forgot going by water. If you please

To rank yourself among my followers,

You shall be welcome, and I'll make your means

Better than any gentleman's I keep.

FRANKLIN

Some twenty mark a year! Will that maintain

Scarlet and gold lace, play at th' ordinary,

And bevers at the tavern?

BEAUFORT

I had thought

To prefer you to have been captain of a ship

That's bound for the Red Sea.

FRANKLIN

What hinders it?

BEAUFORT

Why, certainly, the merchants are possess'd

You have been a pirate.

FRANKLIN

Say I were one still,

If I were past the Line once, why methinks

I should do them better service.

Enter Knavesbee.

BEAUFORT

Pray, forbear.

Here's a gentleman whose business

Must engross me wholly.

[Cressingham takes Franklin aside as Beaufort and Knavesbee

talk.]

CRESSINGHAM

What's he? Dost thou know him?

FRANKLIN

A pox upon him! A very knave and rascal

That goes a-hunting with the penal statutes;

And good for nought but to persuade their lords

To rack their rents, and give o'er housekeeping.

Such caterpillars may hang at their lord's ears

When better men are neglected.

CRESSINGHAM

What's his name?

FRANKLIN

Knavesbee.

CRESSINGHAM

Knavesbee!

FRANKLIN

One that deals in a tenth share

About projections: he and his partners, when

They have got a suit once past the seal, will so

Wrangle about partition, and sometimes

They fall to th' ears about it, like your fencers,

That cudgel one another by patent; you shall see him

So terribly bedash'd in a Michaelmas term

Coming from Westminster, that you would swear

He were lighted from a horse race. Hang him, hang him!

He's a scurvy informer; h'as more cozenage in him

Than is in five travelling lotteries.

To feed a kite with the carrion of this knave

When he's dead, and reclaim her, oh, she would prove

An excellent hawk for talon! H'as a fair creature

To his wife too, and a witty rogue it is,

And some men think this knave will wink at small faults.

But, honest George, what shall become of us now?

CRESSINGHAM

Faith, I am resolv'd to set up my rest

For the Low Countries.

FRANKLIN

To serve there?

CRESSINGHAM

Yes, certain.

FRANKLIN

There's thin commons; besides, they have added one day

More to th' week than was in the creation.

Art thou valiant? Art thou valiant, George?

CRESSINGHAM

I may be, and I be put [to]'t.

FRANKLIN

O never fear that;

Thou canst not live two hours after thy landing

Without a quarrel. Thou must resolve to fight,

Or, like a sumner, thou'lt be bastanado'd

At every town's end. You shall have gallants there

As ragged as the fall o' th' leaf, that live

In Holland, where the finest linen's made,

And yet wear ne'er a shirt. These will not only

Quarrel with a newcomer when they are drunk,

But they will quarrel with any man has means

To be drunk afore them. Follow my council, George,

Thou shalt not go o'er; we'll live here i' th' city.

CRESSINGHAM

But how?

FRANKLIN

How? Why, as other gallants do

That feed high, and play copiously, yet brag

They have but nine pound a year to live on. These have wit

To turn rich fools and gulls into quarter-days,

That bring them in certain payment. I have a project

Reflects upon yon merchant, Master Chamlet,

Shall put us into money.

CRESSINGHAM

What is't?

FRANKLIN

Nay,

I will not stale it aforehand; 'tis a new one.

Nor cheating amongst gallants may seem strange;

Why, a reaching wit goes current on th' Exchange.

Exeunt George Cressingham and Franklin.

KNAVESBEE

O my lord, I remember you and I were students together at Cambridge;

but believe me, you went far beyond me.

BEAUFORT

When I studied there, I had so fantastical a brain, that like

a felfare, frighted in winter by a birding-piece, I could settle

nowhere: here and there a little of every several art, and away.

KNAVESBEE

Now my wit, though it were more dull, yet I went slowly on, and

as diverse others, when I could not prove an excellent scholar,

by a plodding patience I attain'd to be a petty lawyer; and I

thank my dullness for't. You may stamp in lead any figure, but

in oil or quicksilver nothing can be imprinted, for they keep

no certain station.

BEAUFORT

O, you tax me well of irresolution; but say, worthy friend, how

thrives my weighty suit which I have trusted to your friendly

bosom? Is there any hope to make me happy?

KNAVESBEE

'Tis yet questionable, for I have not broke the ice to her; an

hour hence come to my house, and if it lie in man, be sure, as

the law phrase says, I will create you lord paramount of your

wishes.

BEAUFORT

O my best friend, and one that takes the hardest course i' th'

world to make himself so!

[Exit Knavesbee.]

Sir, now I'll take my leave.

SIR FRANCIS

Nay, good my lord; my wife is coming down.

Enter Lady Cressingham and Saunder.

BEAUFORT

Pray, pardon me, I have business so importunes me o' th' sudden,

I cannot stay; deliver mine excuse, and in your ear this: let

not a fair woman make you forget your children.

[Exit.]

LADY CRESSINGHAM

What? Are you taking leave too?

CHAMLET

Yes, good madam.

LADY CRESSINGHAM

The rich stuff[s] which my husband bought of you, the works of

them are too common. I have got a Dutch painter to draw patterns,

which I'll have sent to your factors, as in Italy, at Florence

and Ragusa, where these stuffs are woven, to have pieces made

for mine own wearing of a new invention.

CHAMLET

You may, lady, but 'twill be somewhat chargeable.

LADY CRESSINGHAM

Chargeable! What of that? If I live another year, I'll have

my agents shall lie for me at Paris, and at Venice, and at Valladolid

in Spain, for intelligence of all new fashions.

SIR FRANCIS

Do, sweetest; thou deserv'st to be exquisite in all things.

CHAMLET

The two children to which you are mother-in-law would be repaired

too; 'tis time they had new clothing.

LADY CRESSINGHAM

I pray, sir, do not trouble me with them;

They have a father indulgent and careful of them.

SIR FRANCIS

I am sorry you made the motion to her.

CHAMLET

I have done.

[Aside] He has run himself into a pretty dotage.--

Madam, with your leave.

[Aside] He's tied to a new law and a new wife,

Yet to my old proverb, "Anything for a Quiet Life."

Exit Chamlet.

LADY CRESSINGHAM

Good friend, I have a suit to you.

SIR FRANCIS

Dearest self, you most powerfully sway me.

LADY CRESSINGHAM

That you would give o'er this fruitless, if I may not say this

idle, study of alchemy; why, half your house looks like a glass-house.

SAUNDER

And the smoke you make is a worse enemy to good housekeeping than

tobacco.

LADY CRESSINGHAM

Should one of your glasses break, it might bring you to a dead

palsy.

SAUNDER

My lord, your quicksilver has made all your more solid gold and

silver fly in fume.

SIR FRANCIS

I'll be rul'd by you in anything.

LADY CRESSINGHAM

Go, Saunder, break all the glasses.

SAUNDER

I fly to't.

Exit Saunder.

LADY CRESSINGHAM

Why, noble friend, would you find the true philosopher's stone

indeed, my good housewifery should do it. You understand I was

bred up with a great courtly lady; do not think all women mind

gay clothes and riot: there are some widows living have improv'd

both their own fortunes and their children's. Would you take

my counsel, I'd advise you to sell your land.

SIR FRANCIS

My land!

LADY CRESSINGHAM

Yes, and the manor house upon't: 'tis rotten. Oh, the new-fashion'd

buildings brought from the Hague: 'tis stately! I have intelligence

of a purchase, and the title sound, will for half the money you

may sell yours for, bring you in more rent than yours now yields

you.

SIR FRANCIS

If it be so good a pennyworth, I need not sell my land to purchase

it: I'll procure money to do it.

LADY CRESSINGHAM

Where, sir?

SIR FRANCIS

Why, I'll take it up at interest.

LADY CRESSINGHAM

Never did any man thrive that purchas'd with use-money.

SIR FRANCIS

How come you to know these thrifty principles?

LADY CRESSINGHAM

How? Why, my father was a lawyer, and died in the commission,

and may not I by a natural instinct have a reaching that way?

There are, on mine own knowledge, some divines' daughters infinitely

affected with reading controversies, and that, some think, has

been a means to bring so many suits into the spiritual court.

Pray, be advised, sell your land, and purchase more: I knew a

peddlar by being merchant this way, is become lord of many manors.

We should look to lengthen our estates as we do our lives;

Enter Saunder.

And though I am young, yet I am confident

Your able constitution of body

When you are past fourscore, shall keep you fresh

Till I arrive at the neglected year

That I am past childbearing, and yet [even] there

Quick'ning our faint heats in a soft embrace,

And kindling divine flames in fervent prayers,

We may both go out together, and one tomb

Quit our executors the rites of two.

SIR FRANCIS

Oh, you are so wise and so good in everything:

I move by your direction.

SAUNDER

[Aside] She has caught him!

Exeunt.

II.[i. Knavesbee's house]

Enter Knavesbee and his wife [Sib]. Table.

KNAVESBEE

Have you drunk the eggs and muscadine I sent you?

[SIB]

No, they are too fulsome.

KNAVESBEE

Away, y'are a fool!

[Aside] How shall I begin to break the matter to her?--

I do long, wife.

[SIB]

Long, sir?

KNAVESBEE

Long infinitely.

Sit down; there is a penitential motion in me,

Which if thou wilt but second, I shall be

One of the happiest men in Europe.

[SIB]

What might that be?

KNAVESBEE

I had last night one of the strangest dreams;

Methought I was thy confessor, thou mine,

And we reveal'd between us privately

How often we had wrong'd each other's bed

Since we were married.

[SIB]

Came you drunk to bed?

There was a dream with a witness!

KNAVESBEE

No, no witness.

I dreamt nobody heard it but we two.

This dream, wife, do I long to put in act:

Let us confess each other, and I vow

Whatever thou hast done with that sweet corpse

In the way of natural frailty, I protest

Most freely I will pardon.

[SIB]

Go sleep again!

Was there ever such a motion?

KNAVESBEE

Nay, sweet woman,

And thou wilt not have me run mad with my desire,

Be persuaded to't.

[SIB]

Well, be it your pleasure.

KNAVESBEE

But to answer truly.

[SIB]

O, most sincerely!

KNAVESBEE

Begin then: examine me first.

[SIB]

Why, I know not what to ask you.

KNAVESBEE

Let me see. Your father was a captain: demand of me how many

dead pays I am to answer for in the muster-book of wedlock, by

the martial fault of borrowing from my neighbours.

[SIB]

Troth, I can ask no such foolish questions.

KNAVESBEE

Why then, open confession I hope, dear wife, will merit freer

pardon: I sinn'd twice with my laundress, and last circuit there

was at Banbury a she-chamberlain that had a spice of purity, but

at last I prevailed over her.

[SIB]

O, you are an ungracious husband!

KNAVESBEE

I have made a vow never to ride abroad but in thy company. Oh,

a little drink makes me clamber like a monkey! Now, sweet wife,

you have been an outlier too: which is best feed, in the forest

or in the purlieus?

[SIB]

A foolish mind of you i' this!

KNAVESBEE

Nay, sweet love, confess freely; I have given you the example.

[SIB]

Why, you know I went last year to [Sturbridge] Fair.

KNAVESBEE

Yes.

[SIB]

And being in Cambridge, a handsome scholar, one of [Emmanuel]

College, fell in love with me.

KNAVESBEE

O, you sweet-breath'd monkey!

[SIB]

Go hang, you are so boisterous!

KNAVESBEE

But did this scholar show thee his chamber?

[SIB]

Yes.

KNAVESBEE

And didst thou like him?

[SIB]

Like him! Oh, he had the most enticing'st straw-colour'd beard,

a woman with black eyes would have lov'd him like jet! He was

the finest man, with a formal wit; and he had a fine dog that

sure was whelp'd i' th' college, for he understood Latin.

KNAVESBEE

Pooh waw! This is nothing till I know what he did in's chamber.

[SIB]

He burnt wormwood in't to kill the fleas i' th' rushes.

KNAVESBEE

But what did he to thee there?

[SIB]

Some five-and-twenty years hence I may chance tell you. Fie upon

you! What tricks, what crotchets are these? Have you plac'd

anybody behind the arras to hear my confession? I heard one in

England got a divorce from's wife by such a trick; were I dispos'd

now, I would make you as mad. You shall see me play the changeling.

KNAVESBEE

No, no, wife, you shall see me play the changeling: hadst thou

confess'd, this other suit I'll now prefer to thee would have

been dispatch'd in a trice.

[SIB]

And what's that, sir?

KNAVESBEE

Thou wilt wonder at it four-and-twenty years longer than nine

days.

[SIB]

I would very fain hear it.

KNAVESBEE

There is a lord o' th' court, upon my credit, a most dear, honourable

friend of mine, that must lie with thee. Do you laugh? 'Tis

not come to that; you'll laugh when you know who 'tis.

[SIB]

Are you stark mad?

KNAVESBEE

On my religion, I have past my word for't.

'Tis the Lord Beaufort: thou art made happy forever!

The generous and bountiful Lord Beaufort!

You being both so excellent, 'twere pity

If such rare pieces should not be conferred

And sampled together.

[SIB]

Do you mean seriously?

KNAVESBEE

As I hope for preferment.

[SIB]

And can you lose me thus?

KNAVESBEE

Lose you! I shall love you the better! Why, what's the viewing

any wardrobe or jewel-house without a companion to confer their

likings? Yet now I view thee well, methinks thou art a rare monopoly,

and great pity one man should enjoy thee.

[SIB]

This is pretty!

KNAVESBEE

Let's divorce ourselves so long, or think I am gone to th' Indies,

or lie with him when I am asleep, for some Familists of Amsterdam

will tell you [it] may be done with a safe conscience. Come,

you wanton, what hurt can this do to you? I protest nothing so

much as to keep company with an old woman has sore eyes: no more

wrong than I do my beaver when I try it thus. [He rubs it

against the fur, then smoothes it.] Look, this is all: smooth,

and keeps fashion still.

[SIB]

You are one of the basest fellows.

KNAVESBEE

I look'd for chiding;

I do make this a kind of fortitude

The Romans never dreamt of: and 'twere known,

I should be spoke and writ of when I am rotten,

For 'tis beyond example.

[SIB]

But, I pray, resolve me:

Suppose this done, could you ever love me after?

KNAVESBEE

I protest I never thought so well of thee

Till I knew he took a fancy to thee, like one

That has variety of choice meat before him,

Yet has no stomach to't until he hear

Another praise.

Knock within.

Hark, my lord is coming.

[SIB]

Possible!

KNAVESBEE

And my preferment comes along with him. Be wise, mind your good,

and to confute all reason in the world which thou canst urge against

it. When 'tis done, we will be married again, wife, which some

say is the only supersedeas about Limehouse to remove cuckoldry.

Enter Beaufort.

BEAUFORT

Come, are you ready to attend me to the court?

KNAVESBEE

Yes, my lord.

BEAUFORT

Is this fair one your wife?

KNAVESBEE

At your lordship's service. I will look up some writings and

return presently.

Exit Knavesbee.

[SIB]

[Aside] To see and the base fellow do not leave's alone

too!

BEAUFORT

'Tis an excellent habit this. Where were you born, sweet?

[SIB]

I am a Suffolk woman, my lord.

BEAUFORT

Believe it, every [county] you breathe on is the sweeter for you.

Let me see your hand. [Attempting to take her hand from her

glove] The case is loath to part with the jewel! Fairest

one, I have skill in palmistry.

[SIB]

Good my lord, what do you find there?

BEAUFORT

In good earnest, I do find written here all my good fortune lies

in your hand.

[SIB]

You'll keep a very bad house then; you may see by the smallness

of the table.

BEAUFORT

Who is your sweetheart?

[SIB]

Sweetheart!

BEAUFORT

Yes, come, I must sift you to know it.

[SIB]

I am a sieve too [coarse] for your lordship's manchet.

BEAUFORT

Nay, pray you tell me, for I see your husband is an unhandsome

fellow.

[SIB]

Oh, my lord, I took him by weight, not fashion. Goldsmiths' wives

taught me that way of bargain, and some ladies swerve not to follow

the example.

BEAUFORT

But will you not tell me who is your private friend?

[SIB]

Yes, and you'll tell me who is yours.

BEAUFORT

Shall I show you her?

[SIB]

Yes. When will you?

BEAUFORT

Instantly. [He hands her a mirror.] Look, there you may

see her.

[SIB]

I'll break the glass; 'tis now worth nothing.

BEAUFORT

Why?

[SIB]

You have made it a flattering one.

BEAUFORT

I have a summer-house for you: a fine place to flatter solitariness.

Will you come and lie there?

[SIB]

No, my lord.

BEAUFORT

Your husband has promis'd me. Will you not?

[SIB]

I must wink, I tell you, or say nothing.

BEAUFORT

So, I'll kiss you and wink too. [He kisses her.] Midnight

is Cupid's holiday.

Enter Knavesbee.

KNAVESBEE

[Aside] By this time 'tis concluded.--Will you go, my

lord?

BEAUFORT

[To Sib] I leave with you my best wishes till I see you.

KNAVESBEE

This now, if I may borrow our lawyer's phrase, is my wife's imparlance;

at her next appearance she must answer your declaration.

BEAUFORT

You follow it well, sir.

Exeunt Beaufort and Knavesbee.

[SIB]

Did I not know my husband

Of so base, contemptible nature, I should think

'Twere but a trick to try me; but it seems

They are both in wicked earnest, and methinks

Upon the sudden I have a great mind to loathe

This scurvy, unhandsome way my lord has ta'en

To compass me. Why, 'tis for all the world

As if he should come to steal some apricocks

My husband kept for's own tooth, and climb up

Upon his head and shoulders. I'll go to him;

He will put me into brave clothes and rich jewels:

'Twere a very ill part in me not to go,

His mercer and his goldsmith else might curse me.

And what I'll do here, a' my troth yet I know not.

Women, though puzzl'd with these subtle deeds,

May, as i' th' spring, pick physic out of weeds.

Exit.

[II.ii. Chamlet's shop]

Enter (a shop being discover'd) Water Chamlet, two prentices

George and Ralph.

GEORGE

What is't you lack, you lack, you lack?

Stuffs for the belly or the back?

Silk grogans, satins, velvet fine,

The rosy-colour'd carnadine,

Your nutmeg hue, or gingerline,

Cloth of tissue, or [tabine],

That like beaten gold will shine

In your amorous ladies' eyne,

Whilst you their softer silks do twine:

[Enter Rachel].

What is't you lack, you lack, you lack?

[RACHEL]

I do lack content, sir, content I lack: have you or your worshipful

master here any content to sell?

GEORGE

If content be a stuff to be sold by the yard, you may have content

at home and never go abroad for't.

[RACHEL]

Do, cut me three yards; I'll pay for 'em.

GEORGE

There's all we have i' th' shop; we must know what you'll give

for 'em first.

CHAMLET

Why, Rachel, sweet Rachel, my bosom Rachel,

How didst thou get forth? Thou wert here, sweet Rac,

Within this hour, even in my very heart!

[RACHEL]

Away! Or stay still, I'll away from thee;

One bed shall never hold us both again,

Nor one roof cover us: didst thou bring home--

GEORGE

What is't you lack, you lack, you lack?

[RACHEL]

Peace, bandog!

Bandog, give me leave to speak, or I'll--

GEORGE

Shall I not follow my trade? I'm bound to't,

And my master bound to bring me up in't.

CHAMLET

Peace, good George, give her anger leave;

Thy mistress will be quiet presently.

[RACHEL]

Quiet? I defy thee and quiet too.

Quiet thy bastards thou hast brought home!

GEORGE AND RALPH

What is't you lack, you lack? Etc.

[RACHEL]

Death, give me an ell! Has one bawling cur

Rais'd up another? Two dogs upon me!

And the old bearward will not succour me,

I'll stave 'em off myself. Give me an ell, I say!

GEORGE

Give her not an inch, master; she'll take two ells if you do.

CHAMLET

Peace, George and Ralph; no more words, I charge you.

And Rachel, sweet wife, be more temperate.

I know your tongue speaks not by the rule

And guidance of your heart, when you proclaim

The pretty children of my virtuous

And noble kinswoman, whom in life you knew

Above my praise's reach, to be my bastards.

This is not well, although your anger did it;

Pray, chide your anger for it.

[RACHEL]

Sir, sir, your gloss

Of kinswoman cannot serve turn; 'tis stale

And smells too rank. Though your shop-wares you vent

With your deceiving lights, yet your chamber stuff

Shall not pass so with me, I say, and I will prove--

GEORGE

What is't you lack?

Enter two children [Maria and Edward Cressingham].

CHAMLET

Why, George, I say!

[RACHEL]

Lecher, I say, I'll be divorc'd from thee;

I'll prove 'em thy bastards, and thou insufficient.

Exit Rachel.

MARIA

What said my angry cousin to you, sir?

That we were bastards?

EDWARD

I hope she meant not us.

CHAMLET

No, no,

My pretty cousin, she meant George and Ralph;

Rage will speak anything, but they are ne'er the worse.

GEORGE

Yes, indeed, forsooth, she spoke to us, but chiefly to Ralph,

because she knows he has but one stone.

RALPH

No more of that if you love me, George; this is not the way to

keep a quiet house.

MARIA

Truly, sir, I would not, for more treasure

Than ever I saw yet, be in your house

A cause of discord.

EDWARD

And do you think I would, sister?

MARIA

No, indeed, Ned.

Enter Franklin [disguised as a gentleman] and young Cressingham

disguis'd [as his tailor].

EDWARD

Why did you not speak for me with you then,

And said we could not have done so?

CHAMLET

No more, sweet cousins, now. Speak, George: customers approach.

CRESSINGHAM

[Aside to Franklin] Is the barber prepar'd?

FRANKLIN

[Aside to Cressingham] With ignorance enough to go through

with it. So near I am to him, we must call cousins: would thou

wert as sure to hit the tailor.

CRESSINGHAM

[Aside to Franklin] If I do not steal away handsomely,

let me never play the tailor again.

GEORGE

What is't you lack? Etc.

FRANKLIN

Good satins, sir.

GEORGE

The best in Europe, sir. Here's a piece worth a piece every yard

of him; the King of Naples wears no better silk. Mark his gloss;

he dazzles the eye to look upon him.

FRANKLIN

Is he not gumm'd?

GEORGE

Gumm'd! He has neither mouth nor tooth, how can he be gumm'd?

FRANKLIN

Very pretty!

CHAMLET

An especial good piece of silk; the worm never spun a finer thread,

believe it, sir.

FRANKLIN

[To Cressingham] Gascoyn, you have some skill in it.

CHAMLET

Your tailor, sir?

FRANKLIN

Yes, sir.

CRESSINGHAM

A good piece, sir; but let's see more choice.

RALPH

[Aside to Cressingham] Tailor, drive through; you know

your bribes!

CRESSINGHAM

[Aside to Ralph] Mum: he bestows forty pounds if I say

the word.

RALPH

[Aside to Cressingham] Strike through; there's poundage

for you then.

FRANKLIN

Ay, marry; I like this better. What sayst thou, Gascoyn?

CRESSINGHAM

A good piece indeed, sir.

GEORGE

The great Turk has worse satin at's elbow than this, sir.

FRANKLIN

The price?

CHAMLET

Look on the mark, George.

GEORGE

[Aside to Chamlet] O, souse and P, by my facks, sir.

CHAMLET

The best sort then: sixteen a yard, nothing to be bated.

FRANKLIN

Fie, sir, fifteen's too high! Yet so. [To Cressingham]

How many yards will service for my suit, sirrah?

CRESSINGHAM

Nine yards; you can have no less, Sir Andrew.

FRANKLIN

But I can, sir, if you please to steal less; I had but eight in

my last suit.

CRESSINGHAM

You pinch us too near, in faith, Sir Andrew.

FRANKLIN

Yet can you pinch out a false pair of sleeves to a frizado doublet?

GEORGE

No, sir, some purses and pin-pillows perhaps; a tailor pays for

his kissing that ways.

FRANKLIN

[To Chamlet] Well, sir, eight yards; eight fifteens I

give, and cut it.

CHAMLET

I cannot, truly, sir.

GEORGE

My master must be no subsidy-man, sir, if he take such fifteens.

FRANKLIN

I am at highest, sir, if you can take money.

CHAMLET

Well, sir, I'll give you the buying once; I hope to gain it in

your custom. Want you nothing else, sir?

FRANKLIN

Not at this time, sir.

CRESSINGHAM

Indeed, but you do, Sir Andrew. I must needs deliver my lady's

message to you; she enjoin'd me by oath to do it: she commanded

me to move you for a new gown.

FRANKLIN

Sirrah, I'll break your head if you motion it again.

CRESSINGHAM

I must endanger myself for my lady, sir; you know she's to go

to my Lady Trenchmore's wedding, and to be seen there without

a new gown! She'll have ne'er an eye to be seen there, for her

fingers in 'em. Nay, by my fack, sir, I do not think she'll go,

and then, the cause known, what a discredit 'twill be to you!

FRANKLIN

Not a word more, goodman snipsnapper, for your ears! What comes

this to, sir?

CHAMLET

Six pound, sir.

FRANKLIN

[Giving him money] There's your money. [To Cressingham]

Will you take this and be gone, and about your business presently?

CRESSINGHAM

Troth, sir, I'll see some stuffs for my lady first. I'll tell

her at least I did my good will. [To George] A fair piece

of cloth of silver, pray you now.

GEORGE

Or cloth of gold if you please, sir, as rich as ever the sophy

wore.

FRANKLIN

You are the arrantest villain of a tailor that ever sat cross-legg'd!

What do you think a gown of this stuff will come to?

CRESSINGHAM

Why, say it be forty pound, sir: what's that to you? Three thousand

a year I hope will maintain it.

FRANKLIN

It will, sir; very good. You were best be my overseer! Say I

be not furnish'd with money, how then?

CRESSINGHAM

A very fine excuse in you! Which place of ten now will you send

me for a hundred pound to bring it presently?

CHAMLET

Sir, sir, your tailor persuades you well; 'tis for your credit,

and the great content of your lady.

FRANKLIN

'Tis for your content, sir, and my charges. [To Cressingham]

Never think, goodman falsestitch, to come to the mercers with

me again. Pray, will you see if my cousin Sweetball the barber,

he's nearest hand, be furnish'd, and bring me word instantly.

CRESSINGHAM

I fly, sir.

Exit Cressingham.

FRANKLIN

You may fly, sir; you have clipt somebody's wings for it to piece

out your own. An arrant thief you are.

CHAMLET

Indeed, he speaks honestly and justly, sir.

FRANKLIN

You expect some gain, sir: there's your cause of love.

CHAMLET

Surely I do a little, sir.

FRANKLIN

And what might be the price of this?

CHAMLET

This is thirty a yard; but if you'll go to forty, here's a nonpareil.

FRANKLIN

So, there's a matter of forty pound for a gown cloth.

CHAMLET

Thereabouts, sir. Why, sir, there are far short of your means

that wear the like.

FRANKLIN

Do you know my means, sir?

GEORGE

By overhearing your tailor, sir, three thousand a year; but if

you'd have a petticoat for your lady, here's a stuff.

FRANKLIN

Are you another tailor, sirrah? Here's a knave! What are you?

GEORGE

You are such another gentleman. But for the stuff, sir, 'tis

[L. s. and d.]; for the turn stripp'd a' purpose, a yard and a

quarter broad too, which is the just depth of a woman's petticoat.

FRANKLIN

And why stripp'd for a petticoat?

GEORGE

Because if they abuse their petticoats, there are abuses stripp'd,

then 'tis taking them up, and they may be stripp'd and whipp'd

too.

FRANKLIN

Very ingenious.

GEORGE

Then it is likewise stripp'd standing, between which is discover'd

the open part, which is now call'd the placket.

FRANKLIN

Why, was it ever call'd otherwise?

GEORGE

Yes; while the word remain'd pure in his original, the Latin tongue,

who have no K's, it was call'd the placet, a placendo,

a thing or place to please.

FRANKLIN

Better and worse still.

Enter young Cressingham.

Now, sir, you come in haste; what says my cousin?

CRESSINGHAM

Protest, sir, he's half angry that either you should think him

unfurnish'd, or not furnish'd for your use. There's a hundred

pound ready for you; he desires you to pardon his coming: his

folks are busy and his wife trimming a gentleman, but at your

first approach the money wants but telling.

FRANKLIN

He would not trust you with it. I con him thanks for that: he

knows what trade you are of. [To Chamlet] Well, sir,

pray, cut him patterns; he may in the meantime know my lady's

liking. Let your man take the pieces whole with the lowest prices,

and walk with me to my cousin's.

CHAMLET

With all my heart, sir. Ralph, your cloak, and go with the gentleman;

look you give good measure.

CRESSINGHAM

Look you, carry a good yard with you.

RALPH

The best i' th' shop, sir, yet we have none bad. You'll have

the stuff for the petticoat too?

FRANKLIN

No, sir, the gown only.

CRESSINGHAM

By all means, sir. Not the petticoat? That were holiday upon

working-day, i'faith.

FRANKLIN

You are so forward for a knave, sir!

CRESSINGHAM

'Tis for your credit and my lady's both I do it, sir.

FRANKLIN

[To Chamlet] Your man is trusty, sir?

CHAMLET

O sir, we keep none but those we dare trust, sir! [Aside to

Ralph] Ralph, have a care of light gold.

RALPH

[Aside to Chamlet] I warrant you, sir, I'll take none.

FRANKLIN

Come, sirrah. Fare you well.

CHAMLET

Pray, know my shop another time, sir.

FRANKLIN

That I shall, sir, from all the shops i' th' town. 'Tis the Lamb

in Lombard Street.

Exeunt Franklin, Cressingham, Ralph.

GEORGE

A good morning's work, sir. If this custom would but last long,

you might shut up your shop and live privately.

CHAMLET

O George, but here's a grief that takes away all the gains and

joy of all my thrift!

GEORGE

What's that, sir?

CHAMLET

Thy mistress, George; her frowardness sours all my comfort.

GEORGE

Alas, sir, they are but squibs and crackers; they'll soon die:

you know her flashes of old.

CHAMLET

But they fly so near me that they burn me, George; they are as

ill as muskets charged with bullets.

GEORGE

She has discharg'd herself now, sir; you need not fear her.

CHAMLET

No man can [live] without his affliction, George.

GEORGE

As you cannot without my mistress.

CHAMLET

Right, right, there's harmony in discords: this lamp of love while

any oil is left can never be extinct; it may, like a snuff, wink

and seem to die, but up he will again and show his head. I cannot

be quiet, George, without my wife at home.

GEORGE

And when she's at home, you're never quiet, I'm sure; a fine life

you have on't. Well, sir, I'll do my best to find her and bring

her back if I can.

CHAMLET

Do, honest George, at Knavesbee's house, that varlet's--

There's her haunt and harbour--who enforces

A kinsman on her and [she] calls him cousin.

Restore her, George, to ease this heart that's vex'd;

The best new suit that e'er thou worest is next.

GEORGE

I thank you aforehand, sir.

Exeunt.

[II.iii. Outside Sweetball's house]

Enter Franklin [and] young Cressingham [disguised] as before,

Ralph [carrying the stuffs], [Sweetball the] Barber, Boy.

BARBER

Were it of greater moment than you speak of, noble sir, I hope

you think me sufficient, and it shall be effectually performed.

FRANKLIN

I could wish your wife did not know it, coz. Women's tongues

are not always tuneable; I may many ways requite it.

BARBER

Believe me, she shall not, sir, which will be the hardest thing

of all.

FRANKLIN

Pray you, dispatch him then.

BARBER

With the celerity a man tells gold to him.

FRANKLIN

[Aside] He hits a good comparison! [To Ralph]

Give my waste-good your stuffs and go with my cousin, sir; he'll

presently dispatch you.

RALPH

Yes, sir.

BARBER

Come with me, youth; I am ready for you in my more private chamber.

Exeunt Barber and Ralph.

FRANKLIN

Sirrah, go you show your lady the stuffs, and let her choose her

colour. Away; you know whither. Boy, prithee lend me a brush

i' th' meantime. Do you tarry all day now?

CRESSINGHAM

That I will, sir, and all night too ere I come again.

Exit young Cressingham [with the stuffs].

BOY

Here's a brush, sir.

FRANKLIN

A good child!

BARBER within

What, Toby!

BOY

Anon, sir.

BARBER within

Why, when, goodman picklock?

BOY

I must attend my master, sir. I come!

FRANKLIN

Do, pretty lad.

Exit Boy.

So, take water at Cole Harbour.

An easy mercer and an innocent barber!

Exit Franklin [with the brush].

[II.iv. A chamber in Sweetball's house]

Enter Barber, Ralph, Boy.

BARBER

So, friend, I'll now dispatch you presently. Boy, reach me my

dismembering instrument and let my [cauterizer] be ready, and,

hark you, snip snap!

BOY

Ay, sir.

BARBER

See if my [lixivium], my fomentation be provided first,

and get my rollers, bolsters, and pledgets arm'd.

RALPH

Nay, good sir, dispatch my business first; I should not stay from

my shop.

BARBER

You must have a little patience, sir, when you are a patient;

if [praeputium] be not too much perish'd, you shall lose

but little by it, believe my art for that.

RALPH

What's that, sir?

BARBER

Marry, if there be exulceration between [praeputium] and

glans, by my faith, the whole penis may be endanger'd

as far as os [pubis].

RALPH

What's this you talk on, sir?

BARBER

If they be gangren'd once, testiculi, vesica, and

all may run to mortification.

RALPH

What a pox does this barber talk on?

BARBER

O fie, youth, pox is no word of art: morbus Gallicus, or

Neopolitamus had been well. Come, friend, you must not

be nice; open your griefs freely to me.

RALPH

Why, sir, I open my grief to you: I want my money.

BARBER

Take you no care for that: your worthy cousin has given me part

in hand, and the rest I know he will upon your recovery, and I

dare take his word.

RALPH

'Sdeath, where's my ware?

BARBER

Ware! That was well: the word is cleanly, though not artful.

Your ware is that I must see.

RALPH

My [tabine] and cloth of tissue!

BARBER

You will neither have tissue nor issue if you linger in your malady;

better a member cut off than endanger the whole microcosm.

RALPH

Barber, you are not mad?

BARBER

I do begin to fear you are subject to subeth, unkindly

sleeps, which have bred oppilations in your brain. Take heed,

the symptoma will follow, and this may come to frenzy:

begin with the first cause, which is the pain of your member.

RALPH

Do you see my yard, barber?

BARBER

Now you come to the purpose; 'tis that I must see indeed.

RALPH

You shall feel it, sir. Death, give me my fifty pounds or my

ware again, or I'll measure out your anatomy by the yard!

BARBER

Boy, my cauterizing iron red-hot!

Exit Boy [and re-enter with iron].

BOY

'Tis here, sir.

BARBER

If you go further, I take my dismembering knife.

RALPH

Where's the knight, your cousin? The thief! And the tailor with

my cloth of gold and tissue?

BOY

The gentleman that sent away his man with the stuffs is gone a

pretty while since; he has carried away our new brush.

BARBER

O, that brush hurts my heart's side! Cheated! Cheated! He told

me that your virga had a burning-fever.

RALPH

A pox on your virga, barber!

BARBER

And that you would be bashful and asham'd to show your head.

RALPH

I shall so hereafter, but here it is; you see yet my head, my

hair, and my wit, and here are my heels that I must show to my

master if the cheaters be not found. And barber, provide thee

plasters: I will break thy head with every basin under the pole!

Exit Ralph.

BARBER

Cool the [lixivium] and quench the cauterizer;

I am partly out of my wits and partly mad.

My razor's at my heart: these storms will make

My sweetballs stink, my harmless basins shake.

Exeunt.

III.[i. Lord Beaufort's house]

Enter [Mistress George Cressingham disguised as] Selenger,

[Sib].

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

You're welcome, mistress, as I may speak it,

But my lord will give it a sweeter emphasis.

I'll give him knowledge of you.

Exiturus.

[SIB]

Good sir, stay.

Methinks it sounds sweetest upon your tongue:

I'll wish you to go no further for my welcome.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

Mine! It seems you never heard good music

That commend a bagpipe. Hear his harmony.

[SIB]

Nay, good now, let me borrow of your patience;

I'll pay you again before I rise tomorrow.

If it please you--

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

What would you, forsooth?

[SIB]

Your company, sir.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

My attendance you should have, mistress, but that my lord expects

it, and 'tis his due.

[SIB]

And must be paid upon the hour? That's too strict; any time of

the day will serve.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

Alas, 'tis due every minute, and paid, 'tis due again, or else

I forfeit my recognisance, the cloth I wear of his.

[SIB]

Come, come, pay it double at another time, and 'twill be quitted;

I have a little use of you.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

Of me, forsooth! Small use can be made of me: if you have suit

to my lord, none can speak better for you than you may yourself.

[SIB]

Oh, but I am bashful.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

So am I, in troth, mistress.

[SIB]

Now I remember me: I have a toy to deliver your lord that's yet

unfinish'd, and you may further me. Pray you, your hands, while

I unwind this skein of gold from you; 'twill not detain you long.

[She unwinds the skein around her wrists.]

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

You wind me into your service prettily; with all the haste you

can, I beseech you.

[SIB]

If it tangle not, I shall soon have done.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

No, it shall not tangle if I can help it, forsooth.

[SIB]

If it do, I can help it. Fear not this thing of long length;

you shall see I can bring you to a bottom.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

I think so too: if it be not bottomless, this length will reach

it.

[SIB]

It becomes you finely, but I forewarn you, and remember it, your

enemy gain not this advantage of you: you are his prisoner then,

for look you, you are mine now, my captive manacled; I have your

hands in bondage.

Grasps the skein between [her] hands.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

'Tis a good lesson, mistress, and I am perfect in it; another

time I'll take out this, and learn another. Pray you, release

me now.

[SIB]

I could kiss you now, spite of your teeth, if it please me.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

But you could not, for I could bite you with the spite of my teeth,

if it pleases me.

[SIB]

Well, I'll not tempt you so far; I show it but for rudiment.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

When I go a-wooing, I'll think on't again.

[SIB]

In such an hour I learnt it. Say I should,

In recompense of your hands' courtesy,

Make you a fine wrist-favour of this gold,

With all the letters of your name emboss'd

On a soft tress of hair, which I shall cut

From mine own fillet, whose ends should meet and close

In a fast true-love knot: would you wear it

For my sake, sir?

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

I think not, truly, mistress:

My wrists have enough of this gold already;

Would they were rid on't. Yet, pray you, have done;

In troth, I'm weary.

[SIB]

And what a virtue

Is here express'd in you, which had lain hid

But for this trial. Weary of gold, sir?

Oh, that the close engrossers of this treasure

Could be so free to put it off of hand,

What a new-mended world would here be!

It shows a generous condition in you;

In sooth, I think I shall love you dearly for't.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

But if they were in prison, as I am,

They would be glad to buy their freedom with it.

[SIB]

Surely no: there are that, rather than release

This dear companion, do lie in prison with it;

Yes, and will die in prison too.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

'Twere pity but the hangman did enfranchise both.

Enter Beaufort.

BEAUFORT

Selenger, where are you?

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

E'en here, my lord. Mistress, pray you, my liberty; you hinder

my duty to my lord.

Beaufort puts off his hat.

BEAUFORT

Nay, sir, one courtesy shall serve us both at this time. You're

busy, I perceive; when your leisure next serves you, I would employ

you.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

You must pardon me, my lord; you see I am entangled here. Mistress,

I protest I'll break prison if you free me not; take you no notice?

[SIB]

Oh, cry your honour mercy! You are now at liberty, sir.

[She takes the skein off her wrists.]

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

[Aside] And I'm glad on't; I'll ne'er give both my hands

at once again to a woman's command; I'll put one finger in a hole

rather.

BEAUFORT

Leave us.

[MISTRESS CRESSINGHAM]

Free leave have you, my lord. [Aside] So I think you

may have: filthy beauty, what a white witch thou art!

Exit [Mistress Cressingham].

BEAUFORT

Lady, y'are welcome.

[SIB]

I did believe it from your page, my lord.

BEAUFORT

Your husband sent you to me.

[SIB]

He did, my lord,

With duty and commends unto your honour,

Beseeching you to use me very kindly,

By the same token your lordship gave him grant

Of a new lease of threescore pound a year,

Which he and his should forty years enjoy.

BEAUFORT

The token's true, and for your sake, lady

'Tis likely to be better'd, not alone the lease,

But the fee-simple may be his and yours.

[SIB]

I have a suit unto your lordship too

Only myself concerns.

BEAUFORT

'Twill be granted, sure,

Tho' it out-value thy husband's.

[SIB]

Nay, 'tis small charge:

Only your good will and good word, my lord.

BEAUFORT

The first is thine confirm'd; the second then

Cannot stay long behind.

[SIB]

I love your page, sir.

BEAUFORT

Love him! For what?

[SIB]

Oh, the great wisdoms that

Our grandsires had! Do you ask me reason for't?

I love him because I like him, sir.

BEAUFORT

My page!

[SIB]

In mine eye he's a most delicate youth,

But in my heart a thing that it would bleed for.

BEAUFORT

Either your eye is blinded or your remembrance broken:

Call to mind wherefore you came hither, lady.

[SIB]

I do, my lord: for love, and I am in profoundly.

BEAUFORT

You trifle, sure. Do you long for unripe fruit?

'Twill breed diseases in you.

[SIB]

Nothing but worms

In my belly, and there's a seed to expel them;

In mellow, falling fruit I find no relish.

BEAUFORT

'Tis true, the youngest vines yield the most clusters,

But the old ever the sweetest grapes.

[SIB]

I can taste of both, sir,

But with the old I am the soonest cloy'd:

The green keep still an edge on appetite.

BEAUFORT

Sure you are a common creature.

[SIB]

Did you doubt it?

Wherefore came I hither else? Did you think

That honesty only had been immur'd for you,

And I should bring it as an offertory

Unto your shrine of lust? As it was, my lord,

'Twas meant to you, had not the slippery wheel

Of fancy turn'd when I beheld your page.

Nay, had I seen another before him

In mine eyes better [graced], he had been forestall'd.

But as it is--all my strength cannot help--

Beseech you, your good will and good word, my lord;

You may command him, sir, if not affection,

Yet his body, and I desire but that; do't

And I'll command myself your prostitute.

BEAUFORT

Y'are a base strumpet! I succeed my page?

[SIB]

Oh, that's no wonder, my lord; the servant oft

Tastes to his master of the daintiest dish

He brings to him. Beseech you, my lord.

BEAUFORT

Y'are a bold mischief. And to make me your spokesman,

Your procurer to my servant!

[SIB]

Do you shrink at that?

Why, you have done worse without the sense of ill

With a full free conscience of a libertine.

Judge your own sin:

Was it not worse with a damn'd broking-fee

To corrupt [a] husband, state him a pander

To his own wife, by virtue of a lease

Made to him and your bastard issue, could you get 'em?

What a degree of baseness call you this?

'Tis a poor sheep-steal[er] provok'd by want

Compar'd unto a capital traitor; the master

To his servant may be recompens'd, but the husband

To his wife never.

BEAUFORT

Your husband shall smart for this!

Exit Beaufort.

[SIB]

Hang him, do; you have brought him to deserve it:

Bring him to the punishment; there I'll join with you.

I loathe him to the gallows! Hang your page too;

One mourning gown shall serve for both of them.

This trick hath kept mine honesty secure;

Best soldiers use policy: the lion's skin

Becomes not the body when 'tis too great,

But then the fox's may sit close and neat.

Exit.

[III.ii. A street outside a tavern]

Enter Fleshhook, Counterbuff, and Sweetball the Barber.

BARBER

Now, Fleshhook, use thy talon, set upon his right shoulder; thy

sergeant Counterbuff at the left, grasp in his jugulars; and then

let me alone to tickle his diaphragma.

FLESHHOOK

You are sure he has no protection, sir?

BARBER

A protection to cheat and cozen! There was never any granted

to that purpose.

FLESHHOOK

I grant you that too, sir, but that use has been made of 'em.

COUNTERBUFF

Marry, has there, sir. How could else so many broken bankrupts

play up and down by their creditors' noses, and we dare not touch

'em?

BARBER

That's another case, Counterbuff; there's privilege to cozen:

but here cozenage went before, and there's no privilege for that.

To him boldly! I will spend all the scissors in my shop, but

I'll have him snapp'd.

COUNTERBUFF

Well, sir, if he come within the length of large mace once, we'll

teach him to cozen.

BARBER

Marry, hang him, teach him no more cozenage; he's too perfect

in't already. Go gingerly about it, lay your mace on gingerly,

and spice him soundly.

COUNTERBUFF

He's at the tavern, you say?

BARBER

At the Man in the Moon, above stairs. So soon as he comes down,

and the bush left at his back, Ralph is the dog behind him: he

watches to give us notice; be ready then, my dear bloodhounds.

You shall deliver him to Newgate, from thence to the hangman;

his body I will beg of the sheriffs, for at the next lecture I

am likely to be the master of my anatomy. Then will I vex every

vein about him; I will find where his disease of cozenage lay,

whether in the vertebrae, or in [os coxendix]:

but I guess I shall find it descend from humore, through

the [thorax], and lie just at his fingers' ends.

Enter Ralph.

RALPH

Be in readiness, for he's coming this way, alone too. Stand to't

like gentleman and yeoman: so soon as he is in sight, I'll go

fetch my master.

BARBER

I have had a [conquassation] in my cerebrum ever since

the disaster, and now it takes me again: if it turn to a [megrim],

I shall hardly abide the sight of him.

RALPH

My action of defamation shall be clapp'd on him too; I will make

him appear to't in the shape of a white sheet all embroidered

over with peccavis.

Enter Franklin.

Look about; I'll go fetch my master.

[Exit Ralph.]

COUNTERBUFF

I arrest you, sir.

[Counterbuff and Fleshhook grab Franklin.]

FRANKLIN

Ha! Qui va là? Que pensez-vous faire, messieurs?

Me voulez-vous dérober? Je n'ai point d'argent: je suis

un pauvre gentilhomme français.

BARBER

Whoop! Pray you, sir, speak English. You did when you bought

cloth of gold at six nihils a yard, when Ralph's praeputium

was exulcerated.

FRANKLIN

Que voulez-vous? Me voulez-vous tuer? Le[s] Français

ne sont point ennemis. [Giving them his purse] Voilà

ma bourse; que voulez-vous d'avantage?

COUNTERBUFF

Is not your name Franklin, sir?

FRANKLIN

Je n'ai point de joyaux que cestui-ci, et c'est à monsieur

l'ambassadeur. Il m'envoie à [ses] affaires, et vous empêchez

mon service.

COUNTERBUFF

Sir, we are mistaken, for aught I perceive.

Enter Chamlet and Ralph hastily.

CHAMLET

So, so, you have caught him; that's well. How do you, sir?

FRANKLIN

Vous semblez être un homme courtois; je vous prie entendez

mes affaires: il y a ici deux ou [trois] canailles qui m'ont [assiégé],

un pauvre étranger qui ne leur ai fait nul mal, ni donné

mauvaise parole, ni tiré mon épée. L'un

me prend par une épaule, et me frappe deux livre pesant;

l'autre me tire par le bras, il parle je ne sais quoi. Je leur

ai donné ma bourse, et [s'ils] ne me veulent point laisser

aller; que ferai-je monsieur?

CHAMLET

This is a Frenchman it seems, sirs.

COUNTERBUFF

We can find no other in him, sir, and what that is we know not.

CHAMLET

He's very like the man we seek for, else my lights go false.

BARBER

In your shop they may, sir, but here they go true: this is he.

RALPH

The very same, sir, as sure as I am Ralph: this is the rascal.

COUNTERBUFF

Sir, unless you will absolutely challenge him the man, we dare

not proceed further.

FLESHHOOK

I fear we are too far already.

CHAMLET

I know not what to say to't.

Enter Margarita, a French bawd.

MARGARITA

Bon jour, bon jour, gentilhommes.

BARBER

How now! More news from France?

FRANKLIN

Cette femme ici est de mon pays. Madame, je vous prie leur

dire mon pays; il m'ont [retardé], je ne sais pourquoi.

MARGARITA

Etes-vous de France, monsieur?

FRANKLIN

Madame, [vrai] est que je les ai trompés, et suis arrête,

et n'ai nul moyen d'échapper [qu'en changeant] mon langage.

Aidez-moi en cette affaire. Je vous connois bien, où

vous tenez un bordeau; vous et les votres en serez de mieux.

MARGARITA

Laissez faire à moi. Etes-vous de Lyons, dites-vous?

FRANKLIN

De Lyons, ma chère dame.

Embrace and complement.

MARGARITA

[Mon] cousin! Je suis bien aise de vous voir en bonne disposition.

FRANKLIN

[Ma] cousine!

CHAMLET

This is a Frenchman, sure.

BARBER

If he be, 'tis the likest an Englishman that ever I saw; all his

dimensions, proportions! Had I but the dissecting of his heart,

in capsula cordis could I find it now, for a Frenchman's

heart is more [quassative] and subject to tremor than an Englishman's.

CHAMLET

Stay, we'll further enquire of this gentlewoman. Mistress, if

you have so much English to help us with, as I think you have,

for I have long seen you about London, pray, tell us, and truly

tell us, is this gentleman a natural Frenchman or no?

MARGARITA

Ey, begar, de Frenchman, born à Lyons, my cozin.

CHAMLET

Your cousin? If he be not your cousin, he's my cousin, sure!

MARGARITA

Ey conosh his père, what you call his fadre? He

sell poissons.

BARBER

Sell poisons? His father was a 'pothecary then.

MARGARITA

No, no, poissons, what you call fish, fish.

BARBER

Oh, he was a fishmonger.

MARGARITA

Oui, oui.

CHAMLET

Well, well, we are mistaken, I see; pray you, so tell him, and

request him not to be offended. An honest man may look like a

knave, and be ne'er the worse for't. The error was in our eyes,

and now we find it in his tongue.

MARGARITA

J'essayerai encore une fois, monsieur cousin, pour votre sauveté.

Allez-vous en; votre liberté est suffisante. Je gagnerai

le reste pour mon devoir, et vous aurez votre part à mon

école. J'ai une fille qui parle un peu Français;

elle conversera avec vous à la Fleur-de-Lis en Turnbull

Street. Mon cousin, ayez soin de vous-même, et trompez

ces ignorans.

FRANKLIN

Cousine, pour l'amour de vous, et principalement pour moi,

je suis content de m'en aller. Je trouverai votre école,

et si vos écoliers me sont agréables, je tirerai

à l'épée seule, et si d'aventure je la rompe,

je payerai dix sous. Et pour ce vieux fol, [et ces] deux canailles,

ce poulain Snipsnap, et l'autre bonnet rond, je les verrai pendre

premier que je les vois.

CHAMLET

So, so, she has got him off; but I perceive much anger in his

countenance still. And what says he, madam?

MARGARITA

Moosh, moosh anger, but ey conosh heer lodging shall cool him

very well. Dere is a kinswomans can moosh allay heer heat and

heer spleen; she shall do for my saka, and he no trobla you.

CHAMLET

[Giving her money] Look, there is earnest, but thy reward's

behind. Come to my shop, the Holy Lamb in Lombard Street; thou

hast one friend more than e'er thou hadst.

MARGARITA

Tank u, monsieur; shall visit u. Ey make all pacifie; à

votre service très [humblement], tree, four,

five fool of u.

Exit Margarita.

CHAMLET

What's to be done now?

COUNTERBUFF

To pay us for our pains, sir, and better reward us, that we may

be provided against further danger that may come upon's for false

imprisonment.

CHAMLET

All goes false, I think. What do you, neighbour Sweetball?

BARBER

I must phlebotomise, sir, but my almanac says the sign is in Taurus.

I dare not cut my own throat, but if I find any [precedent] that

ever barber hang'd himself, I'll be the second example.

RALPH

This was your ill [lixivium], barber, to cause all to be

cheated.

COUNTERBUFF

What say you to us, sir?

CHAMLET

Good friends, come to me at a calmer hour;

My sorrows lie in heaps upon me now.

What you have, keep; if further trouble follow,

I'll take it on me: I would be press'd to death.

COUNTERBUFF

Well, sir, for this time we'll leave you.

BARBER

I will go with you, officers; I will walk with you in the open

street though it be a scandal to me, for now I have no care of

my credit. A cacokenny is run all over me.

Exeunt [Barber, Fleshhook, Counterbuff]. Enter George.

CHAMLET

What shall we do now, Ralph?

RALPH

Faith, I know not, sir. Here comes George; it may be he can tell

you.

CHAMLET

And there I look for more disaster still;

Yet George appears in a smiling countenance.

Ralph, home to the shop; leave George and I together.

RALPH

I am gone, sir.

Exit Ralph.

CHAMLET

Now, George, what better news eastward? All goes ill the tother way.

GEORGE

I bring you the best news that ever came about your ears in your

life, sir.

CHAMLET

Thou putst me in good comfort, George.

GEORGE

My mistress, you wife, will never trouble you more.

CHAMLET

Ha? Never trouble me more? Of this, George, may be made a sad

construction; that phrase we sometimes use when death makes the

separation. I hope it is not so with her, George?

GEORGE

No, sir, but she vows she'll never come home again to you, so

you shall live quietly, and this I took to be very good news,

sir.

CHAMLET

The worst that could be, this [candied] poison.

I love her, George, and I am bound to do so.

The tongue's bitterness must not separate

United souls: 'twere base and cowardly

For all to yield to the small tongue's assault;

The whole building must not be taken down

For the repairing of a broken window.

GEORGE

Ay, but this is a principal, sir. The truth is, she will be divorc'd,

she says, and is labouring with her cousin Knave-- What do you

call him? I have forgotten the latter end of his name.

CHAMLET

Knavesbee, George.

GEORGE

Ay, Knave or Knavesbee; one I took it to be.

CHAMLET

Why, neither rage nor envy can make a cause, George.

GEORGE

Yes, sir, not only at your person, but she shoots at your shop

too; she says you vent ware that is not warrantable, braided ware,

and that you give not London measure. Women, you know, look for

more than a bare yard. And then you keep children in the name

of your own, which she suspects came not in at the right door.

CHAMLET

She may as well suspect immaculate truth

To be cursed falsehood.

GEORGE

Ay, but if she will, she will: she's a woman, sir.

CHAMLET

'Tis most true, George. Well, that shall be redress'd:

My cousin Cressingham must yield me pardon;

The children shall home again, and thou shalt conduct 'em, George.

GEORGE

That done, I'll be bold to venter once more for her recovery,

since you cannot live at liberty; but because you are a rich citizen,

you will have your chain about your neck. I think I have a device

will bring you together by th' ears again, and then look to 'em

as well as you can.

CHAMLET

Oh George, amongst all my heavy troubles, this

Is the groaning weight! But restore my wife.

GEORGE

Although you ne'er lead hour of quiet life?

CHAMLET

I will endeavour 't, George. I'll lend her will

A power and rule to keep all hush'd and still.

Eat we all sweetmeats, we are soonest rotten.

GEORGE

A sentence! Pity 't should have been forgotten.

Exeunt.

IV.[i. Sir Francis's house]

Enter Sir Francis Cressingham and a Surveyor [at different

doors].

SURVEYOR

Where's master steward?

SIR FRANCIS

Within. What are you, sir?

SURVEYOR

A surveyor, sir.

SIR FRANCIS

And an almanac-maker, I take it. Can you tell me what foul weather

is toward?

SURVEYOR

Marry, the foulest weather is, that your land is flying away.

Exit Surveyor.

SIR FRANCIS

A most terrible prognostication! All the resort, all the business

to my house is to my lady and master steward, whilst Sir Francis

stands for a cipher. I have made away myself and my power as

if I had done it by deed of gift. Here comes the comptroller

of the game.

Enter Saunder.

SAUNDER

What, are you yet resolved to translate this unnecessary land

into ready money?

SIR FRANCIS

Translate it?

SAUNDER

The conveyances are drawn and the money ready. My lady sent me

to you to know directly if you meant to go through in the sale;

if not, she resolves of another course.

SIR FRANCIS

Thou speakest this cheerfully, methinks, whereas faithful servants

were wont to mourn when they beheld the lord that fed and cherish'd

them, [as] by curst enchantments remov'd into another blood.

Cressingham of Cressingham has continued for many years, and must

the name sink now?

SAUNDER

All this is nothing to my lady's resolution; it must be done or

she'll not stay in England. She would know whether your son be

sent for that must likewise set his hand to th' sale; for otherwise

the lawyers say there cannot be a sure conveyance made to the

buyer.

SIR FRANCIS

Yes, I have sent for him; but I pray thee, think what a hard task

'twill be for a father to persuade his son and heir to make away

his inheritance.

SAUNDER

Nay, for that use your own logic: I have heard you talk at the

sessions terribly against deer-stealers, and that kept you from

being put out of the commission.

Exit Saunder. Enter young Cressingham.

SIR FRANCIS

I do live to see two miseries, one to be commanded by my wife,

the other to be censured by my slave.

CRESSINGHAM

[Kneeling] That which I have wanted long, and has been

cause of my irregular courses, I beseech you let raise me from

the ground.